After a temporary standstill, the longitudinal nutrition/microbiome and the anthropological parts in Laya have garnered a promising pace again during the last two months.

- Wim van Daele

- Sep 26, 2025

- 13 min read

With a standstill of more than two and a half months due to paperwork, the longitudinal nutrition/microbiome and the anthropological parts in Laya have restarted again and have regained a promising pace since the middle of July 2025. Yet, it is still going a little too slow due to the aftereffects of the standstill as well as the sheer logistical complexities in locating and finding respondents as well as in collecting and transporting samples across the high Himalayas of Laya. Notwithstanding our highly complex expeditions, we are happy to announce that we collected around 90 samples and integrated nutri/micro/anthro surveys between 15 July and 22 September 2025!

Immediately after we returned from our cross-sectional study in Laya, where most Research Assistants (RAs) also collected information about the planned whereabouts of the longitudinal participants, we noticed that the list of locations was quite different from the earlier list that we had received. Hence, we immediately started the process for acquiring the letter of support from the Gasa Governor for the updated list of locations, which we received around 22 May 2025, after which we could proceed with the application for the necessary permits, which has taken until 9 July 2025. We are grateful for having received the permits in the end, but the time it has taken has led to a critical gap in our longitudinal study, additional financial losses in the project, and have put considerable pressure to catch up during August and September.

As we expected the paperwork to take its time, we had sent the longitudinal RAs to Buli to join in the cross-sectional study there, but having indications that we could perhaps leave to Laya by the middle of June, I decided to bring them back to give them the necessary rest before starting the intense work in Laya. Since it took much longer than expected, they were virtually on holiday for more than a month paid by the project, which led to additional financial losses. Since they had to be on standby, we could not involve them in the cross-sectional study in the urban food environments which might otherwise have helped to improve the numbers, as discussed in the previous blog.

Once we received the permits on 9 July, two and a half months later than our initially planned start of the longitudinal study, the two remaining longitudinal RAs and I immediately started preparing for our stay in Laya and our departure, buying food supplies and packing all the kits and luggage. Yet, after the 3-week long roadblock which occurred during heavy rainfall 2 June, we were facing a new chainage of 5 roadblocks on the way to Gasa. As it was not entirely clear when it exactly would open, it became complicated to book the transport vehicle and the horses and mules. Our departure thus got further postponed and we left on 12 July in the hope that the main roadblock would be cleared around noon. On the way to that block, we could clearly see the damages from the heavy rain on the road.

It took until 5 pm before we could pass a key roadblock and bypass the other roadblocks via an alternative route. This meant that we had to hike up to Laya in the dark along with several horses.

One might think that, upon arrival, we could immediately start with the sample collection and integrated surveys, but this was not the case. First, after having been two and a half months in lower lying areas, it has taken time to re-adapt to the higher altitude of Laya and especially to adapt to the long hikes to reach the herder sites at an even higher altitude, crossing passes of around 5000 meters above sea level. Second, since we were unable to give clear information to our participants about when we could restart, we lost contact with several of them and lost information about their whereabouts. As such, we were missing out on some key migrations and activities, which were at the core of the longitudinal design examining the influence of shifting dwellings, activities, altitudes and foods on nutrient intake and the gut microbiome. When we arrived, people were spread across the mountains for cordyceps collection and summer herding activities and there it is nearly impossible to reach them by phone to make an appointment. The retracing of our participants took some time and was only a partial success.

Yet, we still retraced quite a number of participants who had returned to Laya after the end of the cordyceps season and thus we first focused on reconnecting with them and conducting surveys and collecting samples during July for the sake of seasonal variation in food intake and the gut microbiome. This was a relative success.

The seasonal variation in food habits comprised a larger proportion of fresh vegetables and foraged edibles compared to other seasons. Foraged foods in this period include predominantly a wide variety of wild mushrooms, including Matsutake, which is called the Buddha’s mushroom. It also includes a wide variety of local medicinal plants and roots, as well as some berries and even seeds used as replacement for grains in times of necessity.

In July, we also did day hikes to the sites that were listed by some of our participants where they would be at this time, but no signs of their presence there, as some had shifted their locations, sometimes even the day before. People are extremely mobile here indeed! However, these hikes to new areas also had their anthropological value as these expanded our understanding of the local cosmologies or worldviews and how food-related hardships and illnesses are explained as consequences of disturbances in relation to the environment, including invisible non-human beings. Polluting certain lakes may cause storms or may make you sick, such as the lake we passed by during one of our attempts to locate one respondent.

After our disappointments in locating the respondents in the nearby herder sites and noticing that we were not yet sufficiently adapted to the altitude for longer multi-day hikes, we had to cancel our plans to try our luck with respondents at the herder sites further away. Hence, during July, we could not yet collect samples and conduct integrated surveys with people residing in more remote herder sites and other mountain sites, where we know the environment, activities, interactions with animals and food intake are different, and that would affect the gut microbiome in different ways. Hence, one of our RAs continued to focus on reconnecting with our respondents instead, and continued collecting samples and conducting surveys within Laya, while I went to Thimphu. This to finalize the urban cross-sectional study, organize the transition of some of our cross-sectional RAs to the longitudinal position, and prepare to return in August with a strengthened team and new supplies, as well as with new materials for the sample collection and maintenance, such as the battery for the -80 freezer for the stabilization of the erratic power supply.

Yet, upon arrival early August, we immediately had further hiccups as it soon became clear that we had to again let two RAs go as their priority was clearly in finding another job as a civil servant, which was incompatible with the heavy work ahead of us in the context of a high time pressure and many unpredictable circumstances. We continued the work on planning and on locating participants and gaining an overview of their whereabouts, so that we could start re-contacting participants in the faraway places and organize these trips, which turned out to become real expeditions. This required training as part of the preparatin, such as in setting up tents and packing bags properly.

We gradually expanded our overview of the whereabouts of most of our respondents through combining telephonic and other ways of contacting people, such as passing on and receiving messages through trading horsemen and porters to and from the herders faraway. We first tried this out with the herder sites nearby and since this proved more successful, we started our sample and data collection nearby. This simultaneously provided us with the opportunity to adapt to higher altitudes before heading out for the tougher expeditions. Yet, several participants dropped out of the study due to changed circumstances and lack of contact during the long standstill, which necessitated the recruitment of new participants during our visits to the herder sites to keep the number at 50 longitudinal participants.

By 10 August, we could finally start preparing the longer expeditions to the higher and faraway herder sites for the sample collection, the integrated surveys, comprising dietary recalls and set of nutritional, anthropological, and microbiome-related questions. This required a final double checking of whereabouts of our participants, and making the necessary preparations, such as finding horsemen, horses and a porter who could also bring us safely to the required sites, buying food supplies, getting the horses’ hoofs ready, and packing our bags properly to prepare for mostly rainy and cold weather.

On 15 August, the first team, Uttam Acharya and I, went to Narithang, a site at around 4800-4900 metres comprising at that time 3 herder camps. According to our information, it is unique to collect stool samples at this high altitude and combine all this nutritional and microbiome work with extensive anthropological fieldwork, so this was perhaps one of the most important of our series of expeditions. To reach Narithang, the hike takes for people from Laya only one day, but for us and foreign well-trained hikers, it takes normally around two days with a stop-over in Rodephu where some of the winter herder sites are located. There, we needed to collect firewood to cook dinner inside an erected building for lodging and cooking, and which also protects against the Himalayan black bears in the area. After collecting (mainly wet) firewood, securing the horses to prevent them running away, we could cook in the dark building filled with smoke, and then eat our rice with a type of spinach with some cheese. Having no electricity and no internet coverage, and getting cold in the evening, we went to sleep at around 7 pm.

The next day while hiking up to Narithang, we had a respondent along the way, where we distributed the kit and, happily, it came at the right time and we could immediately collect the sample and conduct the integrated survey.

It was good that we were no longer working with the cross-sectional kits which must be placed in the -80 freezer within 2 hours. Initially, we planned to work with these kits and carry the freezer, battery and generator on horseback. Yet, during the preparatory research it quickly became clear that this would not work, and happily (especially in view of our recent experiences), we found alternative sample kits that can be stored for a sufficient time at room temperature, so that we could finish the expedition and transfer the samples of our entire journey upon return in Laya to the -80 freezer. So, we had 5 days to collect samples from yak herders and others in Narithang, where we recruited few new participants as well.

During our stay in Narithang, we could regularly observe the passing trains of horses at the peak of this trading season between Laya and Lunana, and to observe the different sites used for earlier cordyceps collection, so as to understand that context better as well even though we missed out on these activities earlier.

So, after a week, we returned back to Laya with a collection of samples and rich data and strengthened social relationships with our participants.

Between 15 August and 20 September 2025, we have organized in total 8 expeditions to Chogotang, Shingtaphu, Narithang, Rodephu, Tshari Jatang, Gangey-Teng, and other sites on the way. These have been intense hikes with several passes of around 5000 meters. In my case, I have hiked 18 days and passed 5 such passes, with the highest reaching 5140 meters.

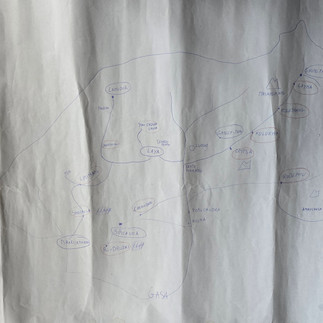

These expeditions combined to different degrees the anthropological study of herder life and the cosmological landscapes, on the one hand, and the nutritional and microbiological aspects of socio-ecological life and dwelling, on the other. It took us to many different people and sites, which has been very illuminating in terms of the variety of herder life depending on locations and other aspects, such as adoption of certain processing technologies, accessibility to food from Laya, internet and phone connectivity, availability of firewood in the vicinity, and the visible and invisible world of other-than-human beings and entities in the area. It also brought us to myths attached to ruins and rocks as well as to various types of camp sites for collection purposes or just for an overnight stay.

One trip also brought us very close to the glaciers of tiger mountain and the physical signs of climate change and the withdrawal of glaciers. Yet, still magical…

During the journeys, we encountered also some of the rich wildlife, some of which used to be eaten as well, but with the ban on killing living animals, this would no longer be the case. In some cases, wildlife affects the herds…

Our aim in these expeditions was indeed to study the inter-relations between yaks, human beings, food, microbes, and other-than-human beings, both anthropologically, nutritionally and microbiologically. Indeed, the intimate relationships between these are likely to create socio-culturally and environmentally patterned circulations of microbes between yaks and human beings through the co-labor in producing food.

In brief, a day in a yak herder camp of a family looks as follows:

The day starts early around 5 am with firing up the firewood to make butter tea, of which several cups are consumed along with zau (puffed rice).

One or several herders will then leave to collect the mother-yaks to reunite them with the children-yaks which are tied to sticks in secure areas, so that they won’t flee and be killed by bears or snow leopards. The small yaks are allowed to drink a little from their mothers and are then separated so that the herder can milk the mother-yaks, and this is repeated up to two times. Thereafter they are released for the day to graze in the nearby area.

When the milking is done and the yaks have left, the herders can prepare breakfast with rice and fresh yak products and limited vegetables, some of which are brought by visitors, like us. By then, several hours have passed since waking up.

Thereafter, mainly the women start the processing of butter and different types of cheese while the men engage in other activities. The processing takes between two and four hours, depending on the methods and technologies used. In the more manual form, which people say is tastier, it takes longer to churn the milk to first make butter, after which the rest-milk is used to boil it to make fresh cheese, with the help of some microbes of fermented rest-milk from earlier times.

In the mechanic churning, the butter is immediately separated from the milk to be boiled for making cheese, and this procedure is much faster, but perhaps less tasty?

After the cheese is prepared, it is squeezed and then put overnight between two flat stones to make chugo cheese which is then cut into smaller pieces and sewed together on a thread.

Other light fermented cheese is made by pouring the fresh milk over branches in a ton, and repeated daily during 10 days or 2 weeks, so that the milk turns into fermented cheese attached to the branches. When it is sufficiently fermented it is taken off and collected in pots.

Depending on the timing, lunch is being prepared during the processing of cheese or after it, and after which there is some time to do other activities until it is time to again collect the mother and children yaks for a new round of milking and securing the children yaks in the safe places for the night. When the evening round of milking is finished, the dinner can be prepared and eaten before going to sleep.

This cycle is repeated every day during this period. A richer description of herder life as well as the influences of these practices on microbial circulations and eventually the human gut microbiome will follow in later publications. The work and life in the herder sites is tough and my respect for the herders has considerably increased by living with them. Staying in tents and simple cabins surrounded by mud in continuous rain and sometimes even sleet has been hard, but I can’t imagine living this life for so many months.

During these expeditions, we also learned soon that the rough picture of herders shifting between summer and winter herder sites was much more complicated than this. First of all, the herders have multiple sites in the summer site between which they switch to according to the availability of grass for grazing and when things get too muddy, so it is sometimes a real challenge to locate them. Moreover, with the onset of the fall, some herders migrate to their intermediate sites where they reside during their transition from summer to winter grazing areas. The dates for shifting the areas and sites are mainly decided according to the astrological calendar, which is updated regularly and at short notice, and depends also on other practical factors such as the availability of food for the yaks. This means that we sometimes arrived at a location finding out that the herders had shifted the day before. It then required some additional hiking to locate them, since most can’t be contacted while in the mountains. As such, we often needed to adapt ourselves to the high mobility of the herders, which sometimes means we cannot collect a sample due to their migration to areas beyond what the permits allow us to visit or due to time pressures in bringing the other samples back to Laya in time. In other cases, we were just in time before the shifting between herder sites, which entailed quite a movement of people, yaks, horses, materials, food items, and probably also microbes.

Our expeditions to conduct the research and collect samples were also not without danger to health and safety.

Several hikes have been marked by nearly continuous rainfall, which made it hard to keep everything dry, especially when camping in tents and living under a blue plastic for cooking and eating. The cold temperatures combined with the humidity made it hard to keep us warm.

The cold was sometimes visible by the fresh snow a little higher up.

The rainfall made some of the water sources for our drinking water and for washing quite troubled by the sand, which my have affected my gut-intestinal functioning.

The rainfall also made several river crossings quite dangerous and sometimes we could not avoid getting soaked. Sometimes, we were offered help from the porter to carry us through the river.

At some occasions, even the horses carrying our luggage had difficulties in crossing the rivers, whereby our luggage with the collected samples got a bathing.

The hikes and camping were sometimes also dangerous for other reasons. Sometimes, we had to climb up very steep mountains sides on slippery rocks, especially while working on the cosmological mapping of the landscape of influences on health and food. Yet, perhaps the biggest danger were the Himalayan black bears. We found fresh signs of their presence many times, several times in the form of footprints and one morning our horseman filmed a bear around 150 meters from our campsite, but unfortunately the quality was too bad to publish here.

Hence, collecting samples and living the herder life in the Bhutanese Himalayas is not a walk in the park!

In the meantime, life in the villages of Laya has also continued and this meant that our work continued there while we were preparing the next expedition.

A key activity in this period has been the preparation of the winter fodder, collecting and drying grass and barley for the horses.

We also participated in and observed several rituals where yak products have a central place in the special foods prepared for these occasions in this period. This meant sometimes very little sleep as some ritual preparations started as early as 1.30 am.

To continue making this longitudinal and anthropological part a success, one of our RAs has started a new expeditions while we others are preparing the next ones after a well-deserved little break.

header.all-comments